Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle

The Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle is an American $20 gold coin. Produced between 1907 and 1933, many people consider it the most beautiful U.S. coin ever made. The St. Gaudens were the last double eagles minted in 1933. This was due to the Gold Confiscation Act removing all gold coinage from circulation.

The relief of the original Saint Gaudens design was too high to strike with coin presses. High-pressure medal presses were required to get a full strike on the coins. These first Ultra High Relief trial pieces are some of the most sought-after U.S. coins in history. The finest 1907 Ultra High Relief double eagles can sell for more than $2 million when they come to auction.

This doesn't mean that a Saint-Gaudens double eagle gold coin is out of your reach. A "Gem Uncirculated" business strike Saint-Gaudens double eagle can be had for around $2,000. Circulated versions are available for a modest premium over spot price.

Modern fascination with the Saint-Gaudens double eagle led to a revival of the design in 1986. The American Gold Eagle debuted as the official gold bullion coin of the U.S. in 1986. The obverse of the American Gold Eagle uses Saint-Gaudens' timeless design.

The Origin of the $20 Double Eagle Coin

The invention of the $20 double eagle gold coin was a direct result of the 1849 California Gold Rush. The unprecedented amount of gold coming from California was more than the U.S. Mint could handle. To ease the situation, the government authorized a new gold coin called the double eagle. The double eagle was twice the weight of the largest gold coin at that time, the $10 gold eagle. This new coin allowed the U.S. Mint to convert twice as much gold into legal tender coins with one strike of a coin press.

The double eagle did not see heavy use in daily commerce. It was instead used to pay for large transactions, such as real estate deals and imports from Europe. International trade of the day was only conducted in gold. Double eagles were also used to back paper gold certificates from 1865 to 1933. These certificates were redeemable for gold coins upon demand.

The Evolution of Saint-Gaudens's Double Eagle Design

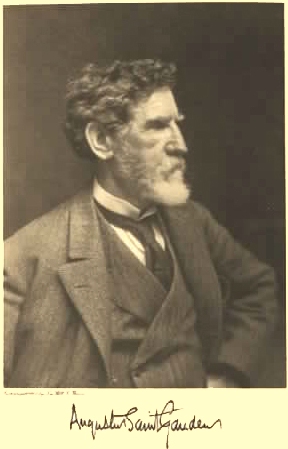

The $20 Saint-Gaudens double eagle is one of the few coins known by the name of its creator. It was designed in 1907 by America's leading Beaux-Arts sculptor, Augustus Saint-Gaudens. In 1905, President Teddy Roosevelt convinced Saint-Gaudens to redesign every U.S. coin. He called existing coins an "atrocious hideousness," unfit for a great nation. He referred to the effort to replace them as his "pet crime."

Saint-Gaudens' death from cancer two years later cut this grand plan short. The only completed designs were the double eagle and $10 gold eagle coins. The design of the double eagle wasn't actually finalized until after his death.

Chief Engraver Charles Barber at the U.S. Mint delayed the production of the coin for as long as he could. Barber was upset that Roosevelt decided to hire Saint-Gaudens to design the new coins. There had never been a US coin that was not designed by Mint engravers. He viewed Roosevelt's decision to hire Saint-Gaudens as a personal affront. Saint-Gaudens had been a vocal critic of Barber's talents for some time. That this opinion was a common one did not lessen the sting to the Chief Engraver's ego.

Roosevelt's condemnation of the currently circulating coin designs heightened Barber's sense of persecution. After all, most of them were his designs. Barber saw Roosevelt's demand to not only replace them all, but to use someone else's designs, as a slap to the face.

Saint-Gaudens's First Double Eagle Designs

The Saint-Gaudens double eagle coin design went through several changes. Saint-Gaudens's first version featured a full-figure winged Liberty. The figure strode toward the viewer with open wings, her gown billowing in the breeze. She held an oval American shield aloft in her left hand and a flaming torch in her right. Saint-Gaudens described the design to President Roosevelt in a 1905 letter. He said, "My idea is to make it a living thing and typical of progress."

The second iteration of the design exchanged the shield for a laurel branch. The Phrygian cap Liberty wore in the initial sketches gave way to an Indian headdress. But the front view of the headdress was too small to be recognizable and was soon omitted. Removing the wings was Saint-Gaudens' last significant change to his design. This move opened up the field of the coin, and put more focus on the figure of Liberty herself.

Finalizing the Design of the Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle

The figure of Liberty was finished at this point, other than a reworking of the folds of her gown. All that remained was the arrangement of the inscriptions that must appear on every U.S. coin.

Saint-Gaudens decided to design his double eagle with as much free space as possible. The deletion of the Indian headdress allowed more room for the word LIBERTY across the top of the coin. He used 46 six-pointed stars, one for each state in the U.S., to make a decorative rim on the obverse. This arch of stars reached from the ground in the lower left of the scene, over Liberty, to the rock on the bottom right.

An eagle flying before a rising sun dominated the design on the reverse. The inscriptions UNITED STATES OF AMERICA and TWENTY DOLLARS ran along the top rim. Saint-Gaudens replaced the vertical grooves (reeding) with the Motto E PLURIBUS UNUM. 13 stars, for the original thirteen colonies of the United States, were also placed on the edge.

Two final design decisions were not Saint-Gaudens's to make. First, he wished to express the date on the new gold double eagle in Roman numerals. He wrote Roosevelt in early 1906, asking if this was possible. The President replied that there was no law forbidding it. If Saint-Gaudens thought his coin looked better with Roman numerals, he was free to use them.

Obverse (front):

"LIBERTY"

Year Minted

An image "emblematic of liberty."

Reverse (back):

Denomination

"UNITED STATES OF AMERICA"

The image of an eagle

Either side or edge:

"E PLURIBUS UNUM"

13 stars for the original colonies

46 stars, one for each state

NOT LEGALLY REQUIRED:

- The Motto "IN GOD WE TRUST."

In God We Trust

The final design decision for the $20 Saint-Gaudens involved the motto IN GOD WE TRUST. The prevailing thought was that the inclusion of this phrase was mandatory on U.S. coins. But an oversight in the Coinage Act of 1873 made its inclusion optional. Section 18 of the Act read, in part:

"and the director of the mint, with the approval of the Secretary of the Treasury, may cause the motto 'In God We Trust' to be inscribed upon such coins as shall admit such motto;"

(In legalese, "shall" is a command. It is mandatory. "May" means it is optional.) No one noticed this mistake until 1907.

Saint-Gaudens desire was to leave the field of the coin uncluttered. He wrote to Roosevelt for guidance. Roosevelt replied that his opinion was that putting the Lord's name on money was "akin to sacrilege." Saint-Gaudens was free to leave the phrase out of his design.

Teddy Roosevelt silver medal

When the Saint-Gaudens $10 and $20 coins were released in late 1907, the public was outraged. Roosevelt unsuccessfully defended his decision to the public. Congress quickly moved to make “In God We Trust” mandatory on all gold and silver coins (but the dime) in early 1908. Today, all coins must bear the motto.

The Struggles Of Turning The Saint-Gaudens Design Into a Coin

Augustus Saint-Gaudens expected hostility from Charles Barber over his ground-breaking coin design. However, the sculptor was wholly unprepared for the technical shortcomings of the mint.

Saint-Gaudens was a world-famous medalist. As such, he was familiar with the capabilities of American medalist firms such as Tiffany and Gorham. He had also spent much of his artistic career in Paris. While there, he took for granted the talents of the many small engravers in the city. These engravers turned sculptors' models into dies ready for striking. During his stays in Paris, the abilities of the French Mint were on constant display. He only had to look at the coins in his pocket to see what a modern mint was capable of. Thus, he expected no severe problems with the U.S. Mint striking his new double eagle design.

The Decision To Make The Saint-Gaudens The First High Relief Coin

Roosevelt and Saint-Gaudens knew that mass-producing high relief coins was impossible. They still decided to make the $20 St. Gaudens Double Eagle America's first high relief coin. This was the genesis of the famous struggles between the sculptor and the U.S. Mint.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens

It was Roosevelt who first proposed making the new gold double eagle in high relief. He wrote Saint-Gaudens asking his opinion:

November 6, 1905

...I was looking at some gold coins of Alexander the Great today, and I was struck by their high relief. Would it not be well to have our coins in high relief, and also to have the rims raised? The point of having the rims raised would be, of course, to protect the figure on the coin. And if we have the figures in high relief, like the figures on the old Greek coins, they will surely last longer. What do you think of this?

Saint-Gaudens replied to the President on November 22, saying:

...I think that something between the high relief of the Greek coins and the extreme low relief of the modern work is possible. And as you suggest, I will make a model with that in view.

The Mint's outdated equipment proved incapable of striking coins at the pressure necessary. Charles Barber made the problems with obtaining a full strike worse. He lacked the skills of the engravers that Saint-Gaudens was used to working with in New York and Paris.

On Barber's part, he had a vested interest in the failure of the coin. If the coin was a success, it was likely that Barber would be excluded in the redesign of other coins. (He was correct.) Barber took every opportunity to emphasize Saint-Gaudens's ignorance of the design constraints. His goal in striking the ultra high relief was to prove that the coin couldn't be minted on a regular coin press.

Saint-Gaudens knew that his initial model could not be struck on a coining press. His purpose in sending this first model to the mint was to learn what their presses were capable of. He wished to see how many strikes it took to get certain features to transfer to the coin blank. He would then change the design and ask for another set of strikes.

This was customary practice when designing a medal or medallion. This was not how circulating coins were made. It was necessary to keep the relief of coin designs as low as possible, to extend the life of the dies. Charles Barber had no artistic training before arriving at the Mint. He was hired by his father, William, who was Chief Engraver of the U.S. Mint at the time. This meant his entire career had been focused on keeping designs as shallow as possible.

Striking the First (Ultra High Relief) Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle

By 1907, Saint-Gaudens's cancer had advanced to the point where he could not stand or walk. As a result, he entrusted the actual modeling work for the double eagle to his assistant Henry Hering. The first ultra high relief trial strikes were struck on February 7, 1907. Hering was present to observe the results.

Hering had been upfront with Barber that this first model was experimental. The goal was to assess how to modify the design without losing details. About half the design transferred to the coin blank on the first strike. The coin was again placed on the die for another strike. Again it showed a little more of the modeling, and so it went on. On the ninth strike, the coin showed up in every detail.

This was not a matter of pressing a button nine times to get nine strikes. The coin blank had to be removed from the medal press after each strike and reheated glowing hot. It was then quenched in a solution of weak nitric acid. After that, it was reinserted in the press and struck again.

The first four Saint-Gaudens double eagles were struck between February 7 and 14, 1907. As this was an experimental design, Barber used the "collar" from his 1906 pattern double eagle. He had also moved E PLURIBUS UNUM to the edge in his 1906 pattern piece, but a year earlier than Saint-Gaudens.

It took many strikes to make a high relief medal (or coin). The procedure was to use a plain collar until the last strike. The lettered (or decorative) collar was then used to finish the coin. The high pressure used on the first ultra high relief Saint-Gaudens double eagles caused the reverse die to crack. This occurred before the fourth coin could be struck the final time. That left this unique coin with a plain edge instead of a lettered edge.

The Second Minting of the Ultra High Relief Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle

Barber continued to experiment with the original Ultra High Relief design. A new die was created, and several Ultra High Relief double eagles struck on the mint's medal presses. It is believed that between 3 and 18 Ultra High Relief double eagles were struck during this period. This included two that were destroyed during testing of the results.

Unlike the original Ultra High Relief coins struck in February, these coins had a new collar. A new serif font replaced the original sans-serif edge lettering. The thirteen stars were now arranged in a long line to fill up the rest of the edge: "⁎E⁎PLURIBUS⁎UNUM⁎⁎⁎⁎⁎⁎⁎⁎⁎⁎" in serif, as compared to the original "⁎E⁎P⁎L⁎U⁎R⁎I⁎B⁎U⁎S⁎U⁎N⁎U⁎M" in san serif.

The Last Three Ultra High Relief Saint-Gaudens Double Eagles

In December, the mint was working around the clock producing High Relief double eagles. They were trying to make enough coins for public release before year's end. In early December, new Director of the Mint Frank Leach asked Barber for a favor. He would like three more 1907 Ultra High Relief double eagles. These last 1907 UHR double eagles would be for new Treasury Secretary Cortelyou, and Saint-Gaudens' widow. Leach would keep the last one for himself.

Federal law mandated that all coin dies be destroyed immediately after the new year. As a result, time was short. Barber requisitioned one of the medal presses and its crew. He struck three 1907 Saint Gaudens Ultra High Relief coins on December 31st.

Shortly after, affairs became more complicated. Roosevelt inquired if there were any more Ultra High Relief coins left, as he desired another one. Leach presented the President with the one earmarked for Mrs. Saint-Gaudens.

It was supposed to be a secret that one last UHR double eagle had been struck for just for her. Regardless, word about the coin reached her. She was understandably upset when it was found that Mint officials received specially minted double eagles, but she did not.

Roosevelt got wind of the controversy in January 1908. He ordered new Ultra High Relief dies prepared expressly to strike a coin for Mrs. Saint-Gaudens. Leach forestalled this drastic measure by suggesting a compromise. One of the two Ultra High Relief coins from the National Coin Cabinet could be given to Mrs. Saint-Gaudens instead.

1921 Saint-Gaudens double eagle

The Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle Enters Production

It wasn't until December 1907 that Saint-Gaudens double eagles entered circulation. These circulation coins are separated into three types:

- Type 1 is the High Relief coins of 1907.

- Type 2 are the 1907 and 1908 "no motto" double eagles, which did not have the motto "In God We Trust."

- Type 3 are the Saint-Gaudens double eagles that have the motto. These were the main production type, running from 1908 until the end of the series in 1933.

The Type 1 High Relief Augustus Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle

The $20 High Relief Saint Gaudens was the first version of the coin released into circulation. The previous Ultra High Relief coins are considered pattern coins. These design tests were not available to the public.

The High Relief double eagles used the second set of models Saint-Gaudens sent to the Mint. These models arrived at the mint in March 1907. The height of the features on this model was not as extreme as the original ultra high relief design. Saint-Gaudens and Henry Hering had expected this version to work on a coin press, but this was not the case. It still took three strikes on a medal press to bring out the details of the coin. Charles Barber had rejected these high relief models out of hand. He was later forced by his new boss, Mint Director Frank A. Leach, to reverse this stance.

Leach had been Superintendent of the San Francisco Mint during the 1906 earthquake. His role in saving the mint led Roosevelt to name him to replace George Roberts as Director of the Mint. Leach was summoned to the White House by an irate Roosevelt as soon as he arrived in Washington. Once there, he received "some details of action of a drastic character for my guidance," according to his memoirs. Many assume this suggestion was to fire Charles Barber. Leach promised to have enough $20 Double Eagles struck for distribution in a month's time.

Leach forced Barber to cut dies from the models he had rejected. The Philadelphia Mint began production of the high relief coins. They used every medal press in their possession. By working extra shifts, 12,367 High Relief coins were delivered to the U.S. Treasury ahead of the deadline.

The need to strike each coin three times on medal presses exposed a defect in some of the lettered collars. The extreme pressure with which the hot coins were struck forced the collar apart. This was enough for some of the gold to squeeze into the gap. This led to a sharp, tiny ridge along the rim on both sides of the coin. Known as "Wire Rim High Reliefs," they commanded premiums from excited collectors.

Barber corrected the "wire rim" defect during the production run. The coins struck from the corrected dies are known as Flat Rim High Reliefs. It is unknown how many Wire Rim versus Flat Rim High Relief double eagles were minted. The great majority of surviving High Relief samples are Wire Rim. This may simply be a result of more Wire Rims being saved due to their novelty.

Few 1907 High Relief Saint-Gaudens double eagles saw circulation. They were snapped up as soon as they arrived at banks, both by collectors and speculators. Within days the new $20 coins were being hawked in the secondary market for $35 or more.

Officials at the time complained that the High Relief coins "would not stack." Modern numismatists thought this meant that the features of the coins protruded above the rim. In retrospect, this made little sense. Saint-Gaudens was one of the best medalists in the world, and would not have made such an obvious mistake. Nor would Barber have allowed such coins to be released.

Research has revealed that the "stacking problem" was due to the rims, but for a different reason. The rims were raised on the High Relief coins so that the features of the coin would not protrude. These raised rims cause the real "stacking problem". A stack of 20 High Relief Saint-Gaudens double eagles was as high as 21 Liberty Head double eagles. Since banks stacked coins to rapidly count them, releasing the coins to the public would cause bedlam. The height of the rims (and features) had to be lowered.

The Type 2 Low Relief Saint-Gaudens Double Eagles

Augustus Saint-Gaudens died from complications from cancer on August 3, 1907. Henry Hering continued the struggle against Charles Barber and the inadequate presses at the U.S. Mint. Hering delivered the third set of double eagle models to Barber in late September. This was before Frank Leach's arrival in Washington, D.C., to take the Mint Director job.

As usual, Barber rejected the models without attempting to use them. Feeling the pressure to get the new double eagles into circulation, he decided to make his own low relief dies. The results were a coin that had lost most of its details, appearing weak even when fully struck.

The most noticeable difference Barber's die and Hering's models was the date. Barber expressed the year date in Arabic numbers, instead of Roman numerals. The MCMVII, while it may have been artistic, did nothing but confuse the public.

Barber's low relief dies were ready in December 1907. For the first time, the $20 St. Gaudens double eagle was struck on high-speed coin presses. Unfortunately, the image bore a weak resemblance to the sculptor's original vision. 361,667 of the 1907 Type 2 "No Motto" Saint-Gaudens double eagles were struck in the last weeks of the year. These are also known as the "Arabic Numerals No Motto" version. This design would be replaced during 1908 with the Type 3 "With Motto" version.

A common practice in the numismatic community is to call the 1907 low relief coins "Saints." Many of these were saved, being the first widespread issue of the iconic coin. But, they did actually enter circulation to some extent. The previous High Relief double eagles vanished into coin collections.

The 1908 No Motto "Wells Fargo" Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle Hoard

The 1908 No Motto Saint-Gaudens double eagle was infamous for poor eye appeal. This changed in the 1990s when 9,900 beautiful Mint State 1908 No Mottos were found in a Nevada bank vault. This became known as the "Wells Fargo Discovery.” These bags contained thousands of pristine 1908 No Motto Saint-Gaudens double eagles. They had remained untouched since 1917.

The Type 3 "With Motto" Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle

Congress passed a law in May 1908, restoring the Motto "In God We Trust" to all gold and silver U.S. coins but the dime. The new dies with the motto were a major improvement over Barber's earlier attempt. The Type 3 "With Motto" double eagles would be the last major change to Saint-Gaudens's design.

Two stars were added to the 46 on the obverse of the coin in 1912, marking the addition of New Mexico and Arizona as states. Instead of making an entirely new hub from scratch, Charles Barber just extended the arc of stars into the landscape on the lower right side. Since gold coins were removed from circulation in 1933, there was never a double eagle with 50 stars. Hawaii and Alaska did not become states until 1959.

Types of Saint-Gaudens Double Eagles

PATTERN = All Ultra High Relief coins, MCMVII No Motto

Mintage: (1907) ~20

TYPE 1 = High Relief, MCMVII No Motto

Mintage: (1907)11,250

TYPE 2 = Low Relief Arabic Numerals No Motto

Mintage (1907 "Saint"): 361,667

(1908): 4,271,551

(1908-D): 663,750

TYPE 3 = With Motto (1908–1933)

The Famous 1933 Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle

The most famous coin of the series is the 1933 Saint-Gaudens double eagle. None of these coins were supposed to have been released to the public. In 1933 Franklin Delano Roosevelt ordered all gold coins pulled from circulation. The US Mint in Philadelphia had already begun double eagle production. Roosevelt's order prevented them from being released into circulation. However, several 1933 double eagles made it into the hands of prominent coin dealers and collectors before the order.

This went unnoticed by the government for several years. That was when a newspaper reporter contacted the Treasury Department in 1944. The reporter was writing a story of a 1933 double eagle up for auction, and was looking for information on the coin. Until this time, the coins had been openly traded without the government noticing.

The Secret Service was now on the case. They tracked down and confiscated every 1933 Saint-Gaudens double eagle they heard about. Several prominent collectors surrendered the ones in their possession. This was despite the large financial loss in doing so. (The government only reimbursed the patriotic coin collectors the $20 face value.)

The King Farouk Double Eagle

The U.S. government has impounded every 1933 double eagle that has appeared in public. This is, except for the one from King Farouk of Egypt's collection. This is the only 1933 Saint-Gaudens double eagle that the government has allowed to be sold.

In 1944, Farouk purchased a 1933 double eagle while visiting the US. He asked the State Department for an export license to take the coin back to Egypt. The State Department, of course, knew nothing about the legality of the coin, and issued the license.

The government soon learned about the 1933 double eagle and asked Farouk to surrender it. As he was a king, he decided not to. Egypt was an important player in WWII and the immediate post-war geopolitical scene. And so, the U.S. government declined to press the matter.

In 1952, Farouk was deposed in a military coup. His extravagant possessions, including his world-class coin collection, was put up for auction. The 1933 Saint-Gaudens double eagle appeared in a 1954 London auction catalog. When the government demanded that the coin be surrendered, it disappeared.

It was next seen in 1996 in the possession of British coin dealer Stephen Fenton. He had flown to New York City to sell the 1933 double eagle to an American buyer. The supposed buyer was a federal agent. Fenton was arrested, and the coin seized.

After years of litigation, the government and Fenton struck a deal. The government would "monetize" the coin, allowing it to be sold. Fenton and the government would split the proceeds from the sale.

Thus, the Farouk 1933 double eagle became the only one of its kind that is legal to own. It was sold at a special Sotheby's auction in 2002. It broke the world record price for a coin, at $7.59 million, including the buyer's premium.

The Langbord 1933 Double Eagle Hoard

Aside from vague whispers, all 1933 double eagles were thought to be accounted for. But, in 2003, Joan and Roy Langbord came forward with ten of the legendary coins. The Langbords were the heirs of famous Philadelphia coin dealer Israel Switt. They had found the coins in an old safe deposit box of Switt's. This was the year after the Farouk 1933 double eagle auction. The Langbords were hoping to get the same 50/50 split that Fenton had negotiated.

Instead, they found themselves caught up in a 14-year battle with the government. They submitted the coins to the U.S. Mint in 2003, asking if they could be authenticated. The mint replied that they were genuine, but were also stolen property. The government seized the ten double eagles, offering no compensation to the Langbords.

The government asserted that Switt had obtained the coins illegally. They claimed he did so with the help of a cashier at the Philadelphia Mint. The Langbords countered that Switt always purchased the new coins from the Mint for his business each year. They said he purchased the ten double eagles at the Mint cashier's window as normal in March 1933. This was before Franklin Roosevelt's Executive Order 6102 removing gold coins from circulation.

The Langbords lost their lawsuit against the government in 2011 and appealed. The three-judge appeals panel ruled in favor of the Langbords. Then the government appealed that verdict. The full court reversed the previous ruling, siding with the government. The Langbords appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, who declined to hear the case.

The Timeless Beauty of the Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle Continues

American Gold Eagle Coin

In 1986 The US Mint started to produce gold coins again and needed inspiration. They could find no more fitting design for America's official gold bullion coin than the Saint-Gaudens double eagle. Since 1986, the American Gold Eagle has been available in BU and Proof versions. The coins are available in sizes ranging from 1 troy ounce to 1/10th troy ounce.

Steven Cochran

A published writer, Steven's coverage of precious metals goes beyond the daily news to explain how ancillary factors affect the market.

Steven specializes in market analysis with an emphasis on stocks, corporate bonds, and government debt.