Estimating the True Size of China’s Gold Reserves

According to my analysis, the Chinese central bank owned 4,309 tonnes of gold on December 31, 2022, which is more than double than what is officially disclosed. My estimate would make China the second largest gold reserve country after the US. The Chinese private sector holds 23,745 tonnes, bringing the total amount of gold in China to 28,054 tonnes.

China and European countries are in agreement to equalize their ratios of monetary gold relative to GDP in order to prepare for a global gold standard.

Introduction

For estimating the true size of the gold reserves of the Chinese central bank (the People’s Bank of China, PBoC), we first need to make a clear distinction between monetary gold (owned by a central bank) and non-monetary gold (owned by the private sector). Without getting into the exact mechanics of the Chinese gold market here, suffice to say that only non-monetary gold imports into China are publicly disclosed. These imports are required to be sold first through the Shanghai Gold Exchange (SGE), and for tax and liquidity reasons virtually all other supply (mine and recycled gold) in China is sold through the SGE as well. On the demand side, private market participants acquire gold at the SGE. It’s unlikely the PBoC buys at the SGE.

Any analysis about the PBoC’s gold reserves based on known import numbers and domestic mine supply is flawed, therefore. It’s true that in the past the PBoC was the primary gold dealer in China—being the monopoly wholesale buyer and seller—but this has changed since the Chinese gold market was liberalized with the launch of the SGE in 2002.

These are the reasons why the PBoC doesn’t buy gold on the SGE:

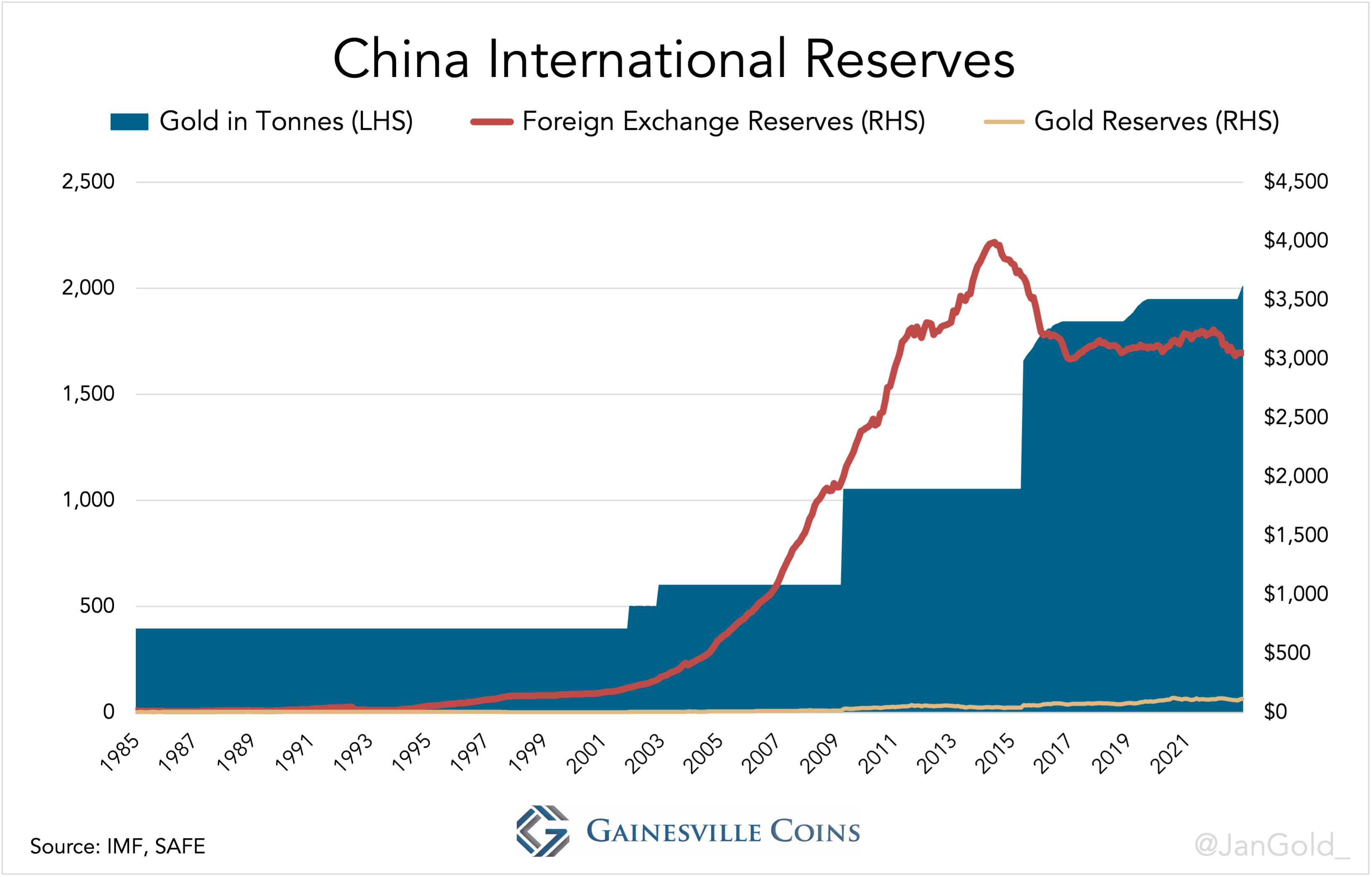

1. The PBoC wants to diversify its foreign exchange reserves—worth more than $3 trillion at the time of writing—by buying gold mainly with US dollars. Gold on the SGE is exclusively quoted in renminbi: not suitable for the PBoC.

2. As we shall see the PBoC prefers to buy gold covertly. If it buys gold abroad with US dollars, the monetary gold is exempt from being reported in international customs data when crossing borders (non-monetary gold is not exempt). Buying abroad allows the PBoC to purchase and repatriate gold without leaving a trace in the public realm.

3. Gold on the SGE often trades at a premium. The PBoC is more likely to buy gold that is priced lower abroad.

4. In 2015 I was in contact with a precious metals trader at a large Chinese state owned bank. He told me that the PBoC buys gold through Chinese proxy banks, such as the one he worked for, in the global OTC market from bullion banks and refineries in, for example, South Africa and Switzerland. Not at the SGE.

Another person I had the opportunity to converse with in 2015, let’s call him Mister-X, worked at one of the big consultancy firms. He was well connected in the industry. Somewhat similar to my Chinese source, he told to me the PBoC uses proxies to purchase gold in the London OTC gold market.

Early 2017, author and gold commentator Jim Rickards met with three heads of the precious metals departments of large Chinese banks. Rickards stated in the Gold Chronicles podcast published January 17, 2017 (25:00):

What I don’t know is about the Shanghai Gold Exchange sales, they’re pretty transparent, how much of that is private and how much of that is the government [PBoC]. And I was sort of guessing 50/50, 70/30, whatever. What they told me, and these guys are the dealers, it’s 100% private. Meaning, the government operates through completely separate channels. The government does not operate through the Shanghai Gold Exchange. … None of what’s going on on the Shanghai Gold Exchange is going to the People’s Bank of China.

Lastly, in 2014 the President of the SGE Transaction Department said in interview:

The PBoC does not buy gold through the SGE.

Until I bump into evidence convincing me of the opposite, my conclusion is the PBoC doesn’t buy gold on the SGE and thus all known supply in China (import, mine output, recycled gold) must be eliminated from our analysis for estimating the PBoC’s true holdings. Most likely, the PBoC buys gold abroad and from there ships it to vaults in Beijing.

Estimating PBoC Gold Reserves

Let us first have a look at what the PBoC has disclosed in the past.

We often see long periods of no purchases and then a sudden large increase in reserves, which suggests they mostly buy by stealth. In June 2015 the Chinese central bank disclosed to have 1,658 tonnes, up from 1,054 tonnes a month prior. Obviously, 604 tonnes weren’t bought in one month.

On one hand the PBoC wants to show the world they are buying gold to catch up with the West, support renminbi internationalization, and move away from the dollar. On the other hand, they don’t want to disclose too much, or they would rock the gold market and drive the price up, which is not in their interest, yet. The Chinese central bank’s interest is to accumulate gold for itself, but it also has a policy of “storing gold among the people” to strengthen China’s economic security (source, page 27). If the price rises, China as a whole can buy less gold.

In March 2013, deputy Chinese central bank governor Yi Gang told the press:

If the Chinese government were to buy too much gold, gold prices would surge, a scenario that will hurt Chinese consumers.

We will always keep gold in mind as an option in reserve assets and investments.

We are able to import 500-600 tons a year, or more, but we will also take into consideration a stable gold market.

Some analysts have interpreted the “500–600 tonnes a year” as what the PBoC buys every single year. It’s more likely, though, Yi referred to the weight imported in 2012 by the Chinese private sector and the PBoC in aggregate. Global cross-border statistics show countries net exported 590 tonnes in non-monetary gold to China in 2012. Add whatever the PBoC bought, and you get “500–600 tonnes a year, or more.”

Another argument why the PBoC doesn’t buy 500 tonnes every year is because the gold market is in constant flux. If the price goes up the PBoC can’t buy much for reasons just mentioned. If the price goes down the PBoC can purchase hundreds of tonnes on sale.

In a previous article I have explained that for at least 90 years the gold price is set in the West. The East dampens volatility by ramping up purchases when the price declines, and lowering purchases when the price rises. Many countries in Asia, like Thailand, even turn into net sellers when the price goes up. This analysis rhymes with Yi’s remarks from 2013: the Chinese don’t set the gold price. (In late 2022 and January 2023 Chinese buying was strong while the price went up, but it’s too soon to confirm a trend reversal.)

After having researched the true size of the PBoC’s gold hoard for some years now, I conclude there is but one approach to get close to what they actually have: through intelligence from those dealing with the PBoC: bullion bankers and people at refineries and secure logistics companies around the world. The following analysis is solely based on industry sources.

Every quarter the World Gold Council (WGC) publishes the Gold Demand Trends (GDT) report, which contains statistics provided by Metals Focus (MF) on mining output, scrap supply, newly fabricated jewelry sold, retail bar demand, ETF hoarding or dishoarding, etc. In these reports there is a single sum divulged for the official sector: a net purchase or sale by all central banks and international financial institutions, such as the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), International Monetary Fund (IMF), and European Central Bank (ECB), combined. This is an estimate based on MF’s field research and doesn’t necessarily align with what central banks openly declare. From the WGC:

Central banks

Net purchases (i.e. gross purchases less gross sales) by central banks and other official sector institutions, including supra national entities such as the IMF. Swaps … are excluded.

A … vital source is confidential information [by MF] regarding unrecorded sales and purchases.

For example, when MF—a consultancy firm in close contact with bullion bankers and people at refineries and secure logistics companies around the world—judges the PBoC bought 50 tonnes in Q1 2023, this tonnage will be attributed to official sector activity in its respective GDT report.

By comparing MF’s official sector estimates to what the official sector publishes, we can deduct what’s bought surreptitiously. People familiar with the matter, but prefer to stay anonymous, told me that the majority of these clandestine acquisitions can be ascribed to the Chinese central bank. Saudi Arabia is also known for buying in secret. Let’s say 80% of the difference between MF’s data and the official numbers released by the IMF are PBoC acquisitions.

Since 2010, when MF’s estimates started, the gross difference has mushroomed to 1,945 tonnes, as can be seen in the chart below.

Mister-X told me in 2015 that it was very difficult for his company to go on record with what they truly think the Chinese central bank owns. The PBoC is very influential and upsetting them would make his company’s operations in the mainland impossible. Though he told me that when the PBoC announced to have 1,658 tonnes in June 2015, his firm estimated that in reality they held twice as much (3,317 tonnes). I’m tempted to believe Mister-X because this tonnage would make more sense than the official number relative to, i.e., China’s vast foreign exchange reserves. If we assume the PBoC held 3,317 tonnes in June 2015, and we add 80% of the furtive investments trailed by MF since then, we arrive at 4,309 tonnes on December 31, 2022.

How much gold did the PBoC buy covertly before 2010? According to my math they did 1,700 tonnes in unreported procurements from the 1990s, when the PBoC held 395 tonnes, until 2010*.

The further back in time the more interesting it gets. After China’s hardline communist leader Mao Zedong died in 1976, a more market oriented economy was structured under the guidance of Deng Xiaoping. Individual gold prospecting was allowed in 1978 (source, page 97), though all output was required to be sold to the PBoC.

In 1983, the Bank of China—the PBoC’s commercial arm that handled overseas operations (source, page 98)—exported 120 tonnes of the PBoC’s gold, sourced from domestic mining, to London to exchange for dollars.

China’s new economic model soon bore fruit. Instead of having to sell domestic mine output to raise foreign exchange, the PBoC was buying gold in London from the Dutch central bank (DNB) in 1992. An article in Dutch Newspaper NRC Handelsblad from March 27, 1993, about a 400 tonnes gold sale from DNB is profoundly informative:

for traders in the international gold market there is no doubt that the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) has bought a part of the 400 tonnes of gold,… which DNB has sold late last year [1992] in utmost secrecy.

“With 99 percent certainty we know that the People’s Bank of China has been one of the buyers of the Dutch gold”, said Philip Klapwijk from Goldfields Mining Services… Also other London bullion dealers have a strong suspicion that China was involved in the gold sales of DNB. “We have noted that the Chinese central bank has bought gold in recent months”, said John Coley of the London bullion dealer Sharp Pixley and spokesman of the London Bullion Market Association.

On 29 September Duisenberg [DNB President] sent a letter to Kok [Dutch Minister of Finance] in which he explained that the sale was intended “to equalize our gold holdings relative to other important gold holding nations.”

Kok agreed on 2 October and in the fall several sales transaction followed in the London forward market. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) acted as an intermediary.

Duisenberg expanded on the gold sales at a BIS meeting on January 12, 1993. The sale had already taken place, only the gold had yet to be delivered. Not all members of the BIS welcomed the Dutch move, nor were they consulted for its decision.

It’s impossible DNB entered the gold market itself because this would immediately leak in the closed world of gold trading. The few remaining Dutch players in the gold market are tiny. In London, there are four major gold traders: Sharps Pixley, Samuel Montague, Mase Westpac and Rothschild. According to John Coley, spokesman of the London Bullion Market Association, it was obvious that DNB would use the BIS as an intermediary. Duisenberg is very well known in Basel because he was President of The Board of the BIS from 1988 to 1990.

“Part of the sale was handled off the market”, says Philip Klapwijk… He says he came to this conclusion because the price of gold last year, although slightly down, should have shown much greater fluctuations if 400 tonnes had been sold in the market…

The BIS probably contacted the People’s Bank of China as the buyer. Why the People’s Republic of China? “The Chinese love gold,” says an expert, and he refers to the huge Taiwanese gold purchases in 1987. Second, China has large dollar surpluses as a result of spectacular economic growth. And third, China announced that it is working to build up its reserves in order to bring it more in line with the size of Chinese GDP.

Presumably, the increase in China’s gold reserves will never be visible. The statistics produced by the IMF for China record the same amount of gold for a decade [395 tonnes] …. China experts, however, know that the People’s Bank has additional secret gold reserves, which are held outside the statistics … If part of the gold reserves of DNB have been added to these, as many suspect, no one will ever officially know.

NRC Handelsblad is a respected newspaper in the Netherlands. Knowledge by industry insiders with respect to covert PBoC acquisitions as early as 1992, may explain how the Chinese central bank had accumulated a total of 3,317 tonnes by 2015. To give you an idea, DNB sold 400 tonnes in 1992 and an additional 700 tonnes in the following years. Other European central banks sold another 3,000 tonnes over this period (“to equalize … gold holdings relative to other important gold holding nations”). Not all could have been bought by the PBoC, but still. In the 1990s the gold price was declining so there were more sellers than buyers: a situation the PBoC has likely exploited.

The PBoC had the opportunity to buy substantial amounts of gold, in and off the market, for decades. It’s not evident all this gold was added to secret monetary reserves, though. Liberalization of the Chinese gold market, initiated in 2002, wasn’t completed until 2007. Chairman of the SGE Shen Xiangrong stated in 2003:

Although four large domestic banks were granted approval to import and export gold back in 2002, they have not yet started these cross-border activities, and the PBOC still remains the only bridge connecting the international bullion market with China.

Any shortfall in domestic mine and scrap supply to meet private demand in the mainland, from 1982 when jewelry sales were first allowed by the Communist Party, up until at least until 2003, was supplemented by gold imports by the PBoC. Even if we knew exactly how much the PBoC imported since 1992, we would only know the amount it accumulated for itself after offsetting those purchases against supply shortfalls in the domestic market.

Estimating China’s Private Gold Reserves

How the Chinese populace has accumulated 23,745 tonnes.

China became a net importer of gold somewhere in the 1990s, according to the China Gold Market Report 2010 that was co-authored by the PBoC. This means Chinese domestic mine production hasn’t crossed a border afterwards.

Precious Metals Insights (PMI) estimates that 2,500 tonnes of gold where held by the population in the mainland in 1994, which is the “jewelry base” we will start off with.

By 2004 the formal prohibition on bullion possession for Chinese people was lifted and private investment took off. In 2007, the Chinese gold market functioned as was intended by the PBoC, as total supply and demand went through the SGE that year for the first time. The China Gold Association (CGA) Yearbook 2007 states (page 39):

2007年,上海黄金交易所黄金入库量394.855 吨,即我国当年的黄金实际供给量

In 2007, the gold storage volume at the Shanghai Gold Exchange was 394.855 tonnes, that is, the actual supply of gold that year …

2007年,上海黄金交易所黄金出库量363.194 吨,即我国当年的黄金需求量,

The amount of gold withdrawn from the warehouses of the Shanghai Gold Exchange in 2007, the total gold demand of that year, was 363.194 tonnes …

因而2007年出现了31.661吨未能交割的库存,

Therefore, there was 31.661 tons of undelivered [SGE] inventory in 2007…

Before 2007 not all supply and demand moved through the SGE, according to CGA Gold Yearbooks, indicating the PBoC was still be involved in the allocation of metal. We shall assume that starting in 2007 the PBoC was no longer interfering in the market.

To calculate private reserves, I have added annual mine production and non-monetary import since 1994 to the jewelry base. From this total I have subtracted openly declared additions by the PBoC from before 2007, because these were presumably sourced, in part, from domestic mines. My methodology is not perfect, but it will do.

The chart below is the result of my calculations on China’s official and private reserves from 1994 through 2022. All shades of blue are private reserves; red is central bank reserves.

Estimated Private and Official Chinese Gold Reserves

Conclusion

All in all, 4,309 tonnes for China’s official gold reserves is the best estimate I can come up with. Not unrealistic, because from the moment China’s economy started expanding in the 1990s, and it ran a persistent current account surplus, it had sufficient foreign exchange reserves to buy gold with, and there was a drive to catch up with other large economies.

There is no doubt in my mind the PBoC bought gold from DNB in 1992. In addition to the evidence in NRC Handelsblad, it’s cited in DNB’s Annual Report 1992 that “demand in the Far-East was strong” when they sold 400 tonnes.

Previously, I have demonstrated on these pages that European central banks have been preparing for a global gold standard since the 1970s through equalizing their monetary gold to GDP ratios. Balanced gold to GDP ratios will smooth the transition to a gold standard (or gold price targeting system) if the current international monetary system is stretched beyond its limits. The Chinese were in on this plan since the 1990s.

China communicated in 1993 (source, NRC Handelsblad) to “build up its [gold] reserves in order to bring it more in line with the size of Chinese GDP.” The significance of this statement is that it can’t be viewed in isolation. Gold is an internationally traded commodity, and its price is the same in everywhere. The Chinese didn’t say, “we aim to have gold reserves worth [i.e.] 10% of our GDP,” because they can buy gold and grow their economy, at the end of the day the gold price is what determines their gold to GDP ratio. What China implicitly said was that it’s aiming to bring its gold to GDP ratio more in line with other countries.

DNB’s Annual Report 1992 states (emphasis mine): “Within the EC [European Community], the Netherlands was and is, when gold reserves are compared to GDP, one of the largest gold holding countries. On this basis, the Bank [DNB] lowered its gold stock from 1707 tonnes to 1307 tonnes in the fall of 1992.” We know DNB eventually lowered its reserves to 612 tonnes, brining it close to the European average (currently 4% of GDP).

In the early 1990s, both the Netherlands and China were candid about equalizing their gold reserves relative to GDP internationally. However, when I asked DNB in 2020 about the reason for past gold sales, they evaded the subject. My question:

Is it true that DNB wanted to achieve a more balanced distribution of official gold reserves worldwide with the sales of its gold since 1992?

Answer:

De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB) weighs several factors in forming an opinion on the total amount of gold in its possession .... We believe that … the current amount [is] balanced at this time. Furthermore, we have no insight into the motivation of other central banks to be able to make statements about their gold reserves and gold policy.

A nonsensical answer because we know gold sales were coordinated in Europe and the overarching policy was balancing reserves.

Why did this become a secret? Duisenberg must have agitated the US when he expanded on DNB’s sales to China at the BIS meeting on January 12, 1993. In NRC Handelsblad we read: “Not all members of the BIS welcomed the Dutch move…” Major economies balancing gold reserves, ready to be deployed during a dollar crisis to transit to new monetary system, is not in America's best interest to say the least. It’s feasible the countries that agreed on balancing gold reserves silenced themselves to avoid conflict with Uncle Sam.

Because we know about an international effort of equalizing reserves, DNB selling gold to China in 1992 made sense as the Netherlands had too much gold (1,707 tonnes) and China too little (395 tonnes), both of their Gross Domestic Product being roughly the same.

On the non-monetary side, China wants private gold reserves to be proportionate to its peers too. Sun Zhaoxue, President of the China Gold Association, wrote in 2012 in Qiushi magazine (the main academic journal of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Committee):

as an important part of China’s gold reserve system, we should also encourage individuals to invest in gold. Practice has proven that private gold reserves are an effective supplement to official reserves and are very important for maintaining national financial security. World Gold Council statistics show that Chinese individuals possess less than 5 grams of gold per capita, a significant difference to the global average of more than 20 grams.

Multiplying 5 grams by 1.3 billion people (the Chinese population in 2012) equals nearly 7,000 tonnes, which matches my estimate of Chinese private reserves held at the end of 2011. My estimate for Chinese private reserves in 2022 is nearly 24,000 tonnes, divided by 1.4 billion people (the Chinese population in 2022), equals 17 grams per capita. China’s non-monetary gold reserves are close to the global average.

China’s monetary gold to GDP ratio (computed with 4,309 tonnes) is 1.5%, which is still lower than 2% in the US and 4% in the eurozone. It’s clear that now is the time for the PBoC to speed up buying. One, China is still behind in its relative gold holdings vis-à-vis Western powers. Two, Russia’s dollar assets were frozen due to the war in Ukraine and the Chinese don’t want to suffer to same fate. Three, the Chinese population has accumulated enough already. Remember Yi Gang was considering private hoarding when he deliberated on how much the PBoC was able to buy in 2013? That doesn’t have to be an issue anymore. Tellingly, the PBoC bought a staggering 522 tonnes in 2022 (based on MF data), which was supportive of the gold price. I think future PBoC procurements, mostly from Russia I suspect, will be supportive of the gold price as well.

Read more from the author about the international gold trade:

Zoltan Pozsar, the Four Prices of Money, and the Coming Gold Bull Market

Governor of Dutch Central Bank States Gold Revaluation Account Is Solvency Backstop

Is the Russian Ruble Linked to Gold?

The West–East Ebb and Flood of Gold Revisited

Is the Gold Price at a Turning Point?

Denmark Releases Gold Bar List, But the Serial Numbers Are Missing

Austrian Monetary Gold Transfer from London to Switzerland—Planned in 2015—Still Hasn't Arrived

Turkish Central Bank Sends Gold To London. In Need for FX?

France Has Repatriated All Its Monetary Gold

What You Need To Know About Physical Gold Supply And Demand

Why Gold Coin Demand Doesn't Drive the Gold Price

.png)