German Central Bank: Gold Revaluation Account Underlines Soundness of Balance Sheet

At a press conference early 2023, member of the Executive Board of the German central bank Joachim Wuermeling made clear that the soundness of the central bank’s balance sheet, in light of general losses, is guaranteed by the bank’s gold revaluation account. Wuermeling’s testimony implies the bank is willing to use its gold revaluation account to cover losses.

The President of the Dutch central bank made a similar remark in November 2022. These statements accentuate gold’s role as a remedy regarding financial challenges created by boundless money printing.

.jpg)

Image: Bundesbank via Flickr

Introduction

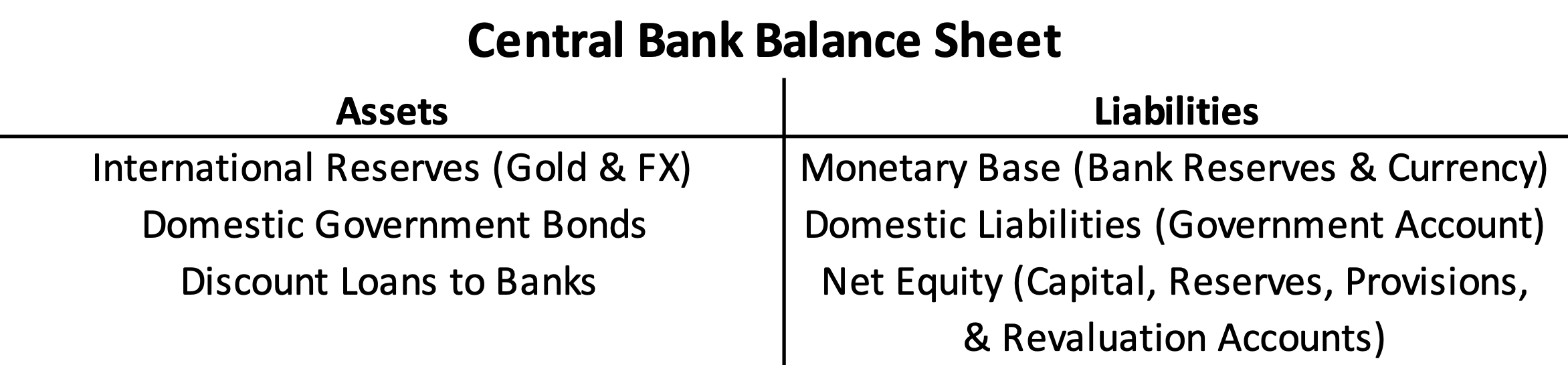

Like many central banks nowadays, the German central bank (Bundesbank, or “Buba” in short) is performing at a loss. Many years of unconventional monetary policy made Buba buy large amounts of German government bonds, carried on the asset side of its balance sheet, with freshly created bank reserves on the liability side. Now interest rates are rising, the interest paid by Buba on its bank reserves liabilities exceeds interest income on its bond portfolio, resulting in a loss that eats into the bank’s capital buffers.

A gold revaluation account (GRA) is an accounting item on the liability side of a balance sheet, part of net equity*, that records unrealized gains of gold assets. Simplified, when the gold price appreciates a GRA swells, and when the price depreciates it contracts.

GRA = Present Gold Value – Historic Gold Purchasing Cost

Because gold is the only international currency that can’t be printed, the gold price denominated in fiat currencies substantially increases in the long run, creating hefty unrealized gains when metal is held for an extended period.

In theory, GRAs can be used by central banks to absorb general losses. Accounting rules, though, determine only capital buffers can be utilized for this purpose, not GRAs. First of all because GRAs are unrealized gains and capital consists of realized gains. Furthermore, suppose a central bank operates at a loss and uses its GRA fully to compensate said losses. Then, the next year the price of gold decreases. With its GRA is emptied, the decline in value of gold assets will be recognized as a loss and can wipe out the bank’s capital buffers. Hence, accounting rules stipulate that GRAs are meant to cushion retracements of the gold price (page 26).

Think of GRAs as part of net equity but shielded from functioning as capital. In the world of accounting, though, nothing is written in stone. Rules can be changed or circumvented, as the central bank of Curaçao and Saint Martin did for using its GRA in 2021.

One could argue that using GRAs to absorb losses is only imprudent if there is a probability that the price of gold can fall below the historic purchasing price. Many European central banks, like the Bundesbank, bought their gold during Bretton Woods for $35 dollars per fine troy ounce and their GRAs are enormous. To the extent the price of gold will never again reach $35 dollars per ounce, it wouldn’t be a sin for Buba to use its GRA. To give you an idea on the Bundesbank’s gold financials:

GRA €176 bn = Present Gold Value €184 bn – Historic Gold Purchasing Cost €8 bn

It can be calculated how much of a GRA can be sapped by estimating a plausible floor for the price of gold in the free market. If the Bundesbank assesses that the price of gold won’t fall below, for example, €400 euros per ounce, it can tap 20% of its GRA (€35 billion). At a floor of €700 euros per ounce, it can use 40% of its GRA (€70 billion), etc.

With this rationale in mind, and more financial stress on the horizon, the German central bank is now publicly taking in consideration to use its GRA for offsetting losses.

Buba’s Press Conference Discussing its Gold Revaluation Account

An article by the Financial Times (FT), published in June 2023, discusses future outcomes if the Bundesbank continues to make losses. Germany’s federal audit office judges (based on EU directives) that if Buba’s losses consume its capital buffers—a situation that may affect the credibility of the Eurosystem’s monetary policy—the German government has to recapitalize its central bank. While the finance ministry believes it’s highly unlikely that losses from the Bundesbank would put a strain on the federal budget.

The article made me research if the FT wasn’t subtly concealing the elephant in the room: the Bundesbank’s gold revaluation account worth €176 billion euros, which, theoretically, can keep the German taxpayer out of the equation.

Eventually I found a recording of Buba’s press conference for the presentation of its Annual Report 2022, held in March 2023. President Joachim Nagel explains in the introduction that the bank is making losses and that “in subsequent years the burdens will probably exceed [the capital] buffers.” Though, he adds: “the Bundesbank’s balance sheet is sound.” Member of the Executive Board Joachim Wuermeling leaves no room for doubt on what guards the soundness of the Bundesbank’s balance sheet: the gold revaluation account. From the horse’s mouth (25:40):

Joachim Wuermeling (member of the Executive Board): What is also of interest is the revaluation accounts. … The most important revaluation item of course is the reserve for the 3,355 tonnes of gold. In fact, the value is about €180 billion euros above the cost of purchasing it, so this is a reserve for us, and it’s part of the considerable own funds of Bundesbank, underlining the soundness which the President mentioned. So, in fact, it’s on firm ground, the balance sheet of Deutsche Bundesbank, and this certainly makes it easier for us to bare losses over a certain period of time.

Why the FT didn’t spell this out is beyond me. Wuermeling literally states, after Nagel noted capital buffers will likely be depleted in coming years, that Buba’s GRA is part of its own funds (capital), which makes it easier to bare losses.

The Bundesbank is two steps ahead by promoting its GRA from part of net equity to own funds. Whatever they may be, Wuermeling is insensitive to the obstacles preventing Buba’s GRA to neutralize losses and guarantee the soundness of its balance sheet.

Source: Bundesbank Annual Report 2022.

As can be seen in the table above, the lion share of Buba’s total revaluation accounts consists of its gold revaluation account. Additionally, in Buba’s Annual Report 2022, it shows its revaluation accounts are an order of magnitude larger than any other component of net equity.

The Bundesbank’s net equity according to the ECB’s definition amounted to €206.5 billion and includes … €19.2 billion contained in liability item 12 “Provisions”, liability item 13 “Revaluation accounts” of €181.7 billion and the capital and reserves of €5.5 billion in total.

No wonder the Bundesbank is willing to use its GRA when confronted with losses.

Conclusion

In February 2022 I asked several central banks in Europe if they considered to write off government bonds to alleviate the debt overhang by using their respective GRAs. The Bundesbank didn’t rule out this possibility. “At this stage, we prefer not to speculate about any potential decisions … that might or might not be taken in the future,” an employee replied. A year later the door to Buba’s GRA has been opened even further.

The barrier for central banks to use their GRAs can, apparently, be overcome. Why else would Buba bring up its GRA regarding losses? And how is the finance ministry so confident it doesn’t have to recapitalize its central bank? All it takes is to change the accounting rules, which central banks do in every crisis, or to find a loophole.

There are important implications to contemplate if major central banks choose this path, though. One, using GRAs emphasizes that fiat currencies devalue against gold through time, stimulating more central banks, corporations, and households to buy gold and reap revaluation benefits in the future as well.

Two, suppose in an extreme scenario Buba uses its entire GRA to cover losses. To avoid its net equity from turning negative, the Bundesbank (/European Central Bank) will need to put a floor under the price of gold, with all due consequences—a gold standard light.

Last but not least, if central banks truly screw up and losses explode, they will need to raise the price of gold to expand their GRAs and mop up all losses. In this scenario a floor under the (new higher) price of gold is required too, for the aforementioned reason. Bear in mind, there is no upper limit to a GRA, as fiat currencies can be printed unrestricted, as opposed to gold.

Using GRAs isn’t a bad thing for the simple reason that it increases gold’s role in the monetary system and has an uplifting effect on the gold price. A higher price deleverages and stabilizes the international monetary system, as it creates a larger base of money without counterparty risk (gold) to support the tower of credit. From an historic perspective that base is relatively small at the time of writing. If additional revaluation advantages can clear more debris from reckless monetary policy in the past, that’s a good thing. This view, coincidentally, rhymes with a quote of the former President of the Bundesbank Jens Weidmann (2018):

Germany’s [gold] reserve assets ... are a major anchor underpinning confidence in the intrinsic value of the Bundesbank’s balance sheet. Gold has grown in importance over the course of history, first as medium of payment, later as the bedrock of stability for the international monetary system.

Notes

* My apologies for any inaccuracies with respect to accounting jargon in my previous articles on gold revaluation accounts. What I have come to understand is that even countries in the same monetary union can each have slightly different approaches to accounting and definitions. Everyone agrees that GRAs are part of net equity, yet the Dutch central bank has mentioned “net equity” where it meant “net financial equity” (a narrower definition of net equity) when discussing its balance sheet. GRAs are not included in the latter.

Further Reading:

- German Central Bank: Gold Is the Bedrock of Stability for the International Monetary System

- German Central Bank Doesn’t Rule Out Gold Revaluation

- Governor Dutch Central Bank States Gold Revaluation Account Is Solvency Backstop

- The Hierarchy of Money and the Case for $8,000 Gold

- How a Central Bank in the Caribbean Recently Used Its Gold Revaluation Account to Cover Losses